Vegan Australia recently made a submission to a Productivity Commission inquiry into mental health. The submission detailed how a whole food plant based (vegan) diet can positively affect the mental health of Australians. It also made recommendations to improve access to healthy vegan food for all Australians, both for prevention and management of mental ill-health.

Please read the submission below.

Vegan Australia is pleased to have the opportunity to provide a submission in response to the issues paper on mental health released by the Productivity Commission. We welcome the opportunity to make recommendations to improve the mental health of Australians and we hope this submission assists in the preparation of the final document.

Vegan Australia is a national organisation that informs the public about animal rights and veganism and also presents a strong voice for veganism to government, institutions, corporations and the media. Vegan Australia envisions a world where all animals live free from human use and ownership. The foundation of Vegan Australia is justice and compassion, for animals as well as for people and the planet. The first step each of us should take to put this compassion into action is to become vegan and to encourage others to do the same. Veganism is a rejection of the exploitation involved in commodifying and using sentient beings.

This submission is mainly in response to the section on specific health concerns in the issues paper. We will provide evidence on how a whole food plant based (vegan) diet can positively affect the mental health of Australians and we will make recommendations to improve access to healthy vegan food for all Australians, both for prevention and management of mental ill-health.

While the issues paper mentions the positive influence of a healthy diet on mental health, we believe a much greater emphasis should be placed on this, including education about nutrition, practical assistance and provision of healthy vegan foods. An important factor in mental health is physical health, which in turn is based largely on a healthy diet.

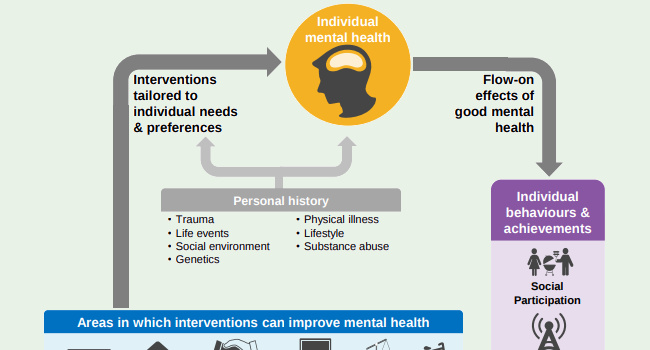

Vegan Australia does not claim to be expert in the field of mental health generally. However we do recognise that promoting a healthy diet must be part of range of evidence based interventions, including therapies of various kinds, exercise, mindfulness, interpersonal skills, social participation, housing assistance, and employment support. Our role is to raise awareness about the link between diet and health.

In this submission we look at how a healthy vegan diet can directly improve mental health and also how this diet can lower the risk of a number of chronic physical diseases and hence indirectly improve mental health. The evidence for these is given in the following sections. We will conclude with a number of recommendations to improve population mental health. We will start with an outline of how a healthy vegan diet can support general health.

There is a common misconception amongst both the general population and health professionals that the consumption of animal products is necessary for health.

A well planned 100% plant based diet is healthy. This is confirmed by a solid body of peer-reviewed scientific evidence. Not only is a plant based diet as healthy as any diet containing animal products, in many aspects it is more beneficial to human health. It can help people live a longer, healthier life, and significantly reduce the risk of falling victim to many of the serious health threats facing Australians today.

Australia's peak health body, the National Health and Medical Research Council, recognises that vegan diets are healthy and nutritionally adequate and are appropriate for individuals of all ages. Alternatives to animal foods, such as nuts, seeds, legumes, beans and tofu, "increase dietary variety and can provide a valuable, affordable source of protein and other nutrients." The Australian Dietary Guidelines state:

"Appropriately planned vegetarian diets, including total vegetarian or vegan diets, are healthy and nutritionally adequate. Well-planned vegetarian diets are appropriate for individuals during all stages of the lifecycle. Those following a strict vegetarian or vegan diet can meet nutrient requirements as long as energy needs are met and an appropriate variety of plant foods are eaten throughout the day. Those following a vegan diet should choose foods to ensure adequate intake of iron and zinc and to optimise the absorption and bioavailability of iron, zinc and calcium. Supplementation of vitamin B12 may be required for people with strict vegan dietary patterns." p35

"Nuts and seeds are rich in energy (kilojoules) and nutrients, reflective of their biological role in nourishing plant embryos to develop into plants. In addition to protein and dietary fibre, they contain significant levels of unsaturated fatty acids and are rich in polyphenols, phytosterols and micronutrients including folate, several valuable forms of vitamin E, selenium, magnesium and other minerals. They are nutritious alternatives to meat, fish and eggs, and play an important role in plant-based, vegetarian and vegan meals and diets.

"Legumes/beans, including lentils, tofu and tempeh, provide a valuable and cost-efficient source of protein, iron, some essential fatty acids, soluble and insoluble dietary fibre and micronutrients. They are valuable inclusions in any diet, and are especially useful for people who consume plant-based meals." p49

The Dietitians Association of Australia, representing over 6,400 members in the dietetic profession, states

With planning, those following a vegan diet can cover all their nutrient bases...

The Dietitians Association of Australia highlights four nutrients vegans should be aware of. Iron: "can get enough through plant foods". B12: eat fortified foods or take a supplement. Calcium: select from a range of "good plant sources of calcium". Omega-3 fats: select from plant sources or supplement with "vegan marine omega-3 fat supplements".

Healthdirect, the national, government-funded health information service, has published an article stating that a vegan diet can help reduce the risk of disease. The article says that "Plant-based diets can help reduce your risk of disease and provide you with all the protein, minerals and vitamins your body needs." It continues: "A vegetarian diet based on vegetables, legumes, beans, wholegrains, fruits, nuts and seeds can help reduce the risk of heart disease, type 2 diabetes, obesity and some types of cancer. Dietary fibre in a plant-based diet increases 'good' bacteria in the bowel."

Australia's top health experts agree with those in other parts of the world that well-planned vegan diets are safe and healthy for all age groups. The Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics (USA) has an even clearer message:

"It is the position of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics that appropriately planned vegetarian, including vegan, diets are healthful, nutritionally adequate and may provide health benefits for the prevention and treatment of certain diseases. These diets are appropriate for all stages of the life cycle, including pregnancy, lactation, infancy, childhood, adolescence, older adulthood and for athletes. Plant-based diets are more environmentally sustainable than diets rich in animal products because they use fewer natural resources and are associated with much less environmental damage. Vegetarians and vegans are at reduced risk of certain health conditions, including ischemic heart disease, type 2 diabetes, hypertension, certain types of cancer, and obesity. Low intake of saturated fat and high intakes of vegetables, fruits, whole grains, legumes, soy products, nuts, and seeds (all rich in fiber and phytochemicals) are characteristics of vegetarian and vegan diets that produce lower total and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels and better serum glucose control. These factors contribute to reduction of chronic disease. Vegans need reliable sources of vitamin B-12, such as fortified foods or supplements."

- Position of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics on Vegetarian Diets

This reflects the Academy's position given in 2003 and again in 2009. This indicates that health experts have acknowledged for many years that vegan diets can be healthy.

In the UK, the NHS statement on vegan diets says "with good planning and an understanding of what makes up a healthy, balanced vegan diet, you can get all the nutrients your body needs" and gives suggestions on how to eat a healthy vegan diet. The British Dietetic Association says "It is possible to follow a well-planned, plant-based, vegan-friendly diet that supports healthy living in people of all ages" and "a balanced vegan diet can be enjoyed by children and adults, including during pregnancy and breastfeeding."

The Canadian Paediatric Society states that "Well-planned vegetarian and vegan diets with appropriate attention to specific nutrient components can provide a healthy alternative lifestyle at all stages of fetal, infant, child and adolescent growth."

Not only are animal products unnecessary for optimal health, an increasing number of nutritionists and health professionals are acknowledging animal products are harmful to our health (see Physicians Committee for Responsible Medicine). This is supported by decades of good research (see Nutrition Facts and Dr McDougall's Health & Medical Centre). A healthy vegan diet helps reduce the risk of heart disease, stroke, cancer, obesity, and diabetes, some of Australia's top killers.

The October 2013 issue of the Medical Journal of Australia, dedicated to the question "Is a Vegetarian [including vegan] Diet Adequate?", included the following statements:

The China Study by Dr T Colin Campbell is one of the most comprehensive studies on nutrition ever done. Campbell provides compelling evidence linking animal products to disease, including cancer, heart disease, osteoporosis, diabetes.

A vegan diet is not a miracle cure for all health issues and it is possible to eat an unhealthy vegan diet, especially if too much processed food is eaten or if the intake of Vitamin B12 and other important nutrients is not adequate. People can stay healthy by eating a wide variety of whole foods such as fruits, vegetables, grains, beans, nuts and seeds.

Full references for this section can be found here: https://veganaustralia.org.au/health

Forty-five percent of adult Australians aged 16-85 years will suffer from a mental illness at some point in their lifetime. Mental disorders may include depression, obsessive-compulsive disorder, schizophrenia, generalised anxiety and eating disorders. If left untreated, many disorders may increase in severity or even lead to suicide. Life is undoubtedly difficult for people affected by mental illness; they need to deal with the disorder in order to function in their everyday lives, and cope with the financial expense of getting treatment. Whilst the Australian Government subsidises some mental health care costs, the burden on the community and individuals alike, is rising. On a positive note, mental illness like many physical illnesses, may improve under a well balanced whole food plant based (vegan) diet. A number of studies have been carried out highlighting the significant difference in the mental wellbeing of participants who were eating a vegan diet compared to those who were not.

According to the Australian Bureau of Statistics, the annual cost of mental illness in Australia for 2007 was $20 billion. This figure includes the cost of lost productivity and labour force participation. In the same period, aside from the direct effect of population growth, the overall number of mental health services subsidised by Medicare doubled to nearly 4 million cases, and State and Territory mental health service expenditure as a whole increased to $3 billion. Similarly, the number of GP visits for mental health reasons in 2007 was estimated at nearly 12 million. Based on the 2007 data on the growth rate of mental health costs, it is estimated that the total cost in Australia has now reached $30 billion.

Exploring possible links between vegan diets and mental wellbeing, the Nutritional Neuroscience Journal recently published findings from a study that investigated the difference in mood amongst selected participants. The mood of 602 subjects (283 vegans, 109 vegetarians and 228 omnivores) was measured using the Depression Anxiety Stress Scale-21 (DASS-21). The results of the study indicate that female vegans report significantly lower average scores in stress compared to non-vegans, whilst male vegans report lower average anxiety scores.

In 2015, a separate study examining whether a plant-based diet improves depression, anxiety and productivity was published in the American Journal of Health Promotion. The study incorporated 10 worksites of a major US insurance company and 292 subjects with a Body Mass Index (BMI) greater than 25, and/or a previous diagnosis of Type 2 diabetes. Some participants were given instructions to follow a vegan diet for 18 weeks and some were given no instructions. Their mood was measured using the Short Form-36 questionnaire, whilst work productivity was measured using the Work Productivity and Impairment questionnaire. Those who were in the intervention group reported significantly improved depression, anxiety and productivity compared to those in the control group.

A recent meta-analysis of data from 16 randomised controlled trials on a total of nearly 46,000 participants found that dietary interventions that aim to decrease the intake of unhealthy foods, improve nutrient intake, and/or produce weight loss reduce symptoms of depression across the population. While only one dietary intervention was completely plant-based, all counselled participants to decrease their intake of ultraprocessed foods such as packaged snacks, pre-prepared meals, instant noodles, soft drinks and ice cream, as well as most animal products, and to eat more fruits, vegetables and whole grains. In some studies, participants were also instructed to eat more nuts and seeds.

A study by the National Bureau of Economic Research, Is Psychological Well-being Linked to the Consumption of Fruit and Vegetables?, found a link between the consumption of fruit and vegetables and high well-being. To quote, "In cross-sectional data, happiness and mental health rise in an approximately dose-response way with the number of daily portions of fruit and vegetables. The pattern is remarkably robust to adjustment for a large number of other demographic, social and economic variables. Well-being peaks at approximately 7 portions per day. We document this relationship in three data sets, covering approximately 80,000 randomly selected British individuals, and for seven measures of well-being (life satisfaction, WEMWBS mental well-being, GHQ mental disorders, self-reported health, happiness, nervousness, and feeling low). Reverse causality and problems of confounding remain possible. We discuss the strengths and weaknesses of our analysis, how government policy-makers might wish to react to it, and what kinds of further research - especially randomized trials - would be valuable."

Dr. Mujcic, a health economist and researcher from University of Queensland, found that people who ate 10 servings of fruits and vegetables per day are happier than those who did not. The study was based on an annual longitudinal household survey in Australia with approximately 12,000 households or individuals. The study examined the participants' choices of fruits and vegetables, and rated their levels of satisfaction, stress, vitality and other mental health markers. The more fruits and vegetables people ate, the better they feel, with 10 servings being the optimal point. The effects were strongest among women for unknown reasons.

And yet, a typical western diet many Australians follow usually includes meat, fish and poultry. A meat-based diet is high in arachidonic acid (AA) which is mainly found in chicken and eggs. AA is known to contribute to brain changes and inflammation, which in turn have been known to adversely affect mood. On the other hand, a diet full of whole plant foods such as fruits, vegetables, nuts and seeds contain an abundance of vitamins and phytonutrients which promote a healthy brain. Nerve cells in the brain communicate with one another through chemical signals called neurotransmitters which include serotonin, dopamine and norepinephrine. Serotonin plays a major role in stabilising mood and balancing excitatory neurotransmitters, namely dopamine and norepinephrine. Dopamine is responsible for driving motivation and improving focus, whilst norepinephrine is responsible for energy level, focus ability and sleep cycle. Higher levels of these neurotransmitters are associated with increased focus, motivation and higher energy.

For nerve cells to communicate, one nerve cell would release neurotransmitters to another nerve cell. The first nerve cell would then collect these chemicals back to be reused whilst producing an enzyme, monoamine oxidase (MOA), to remove excess neurotransmitters. People who suffer from depression appear to have chemical imbalance and elevated level of the MOA enzyme and in effect, the level of neurotransmitters drop and resulted in poorer mood. Many plants and spices are inhibitors of the enzyme. For that reason, vegans who are on a whole food plant based diet, are benefiting from healthier physique and mind, due to having the right balance of chemicals in their brains.

Whilst there is a broader, general concern about possible links between depression and deficiencies in vitamins B12 and D and omega-3 fats, this concern applies to both plant-based and meat-based diets and should be monitored in a wider general health context.

It would be desirable to quantify the financial benefits to society arising from improved mental health due to higher consumption of plant-based foods. However, there is not yet enough reliable research data to make an accurate estimate. It is possible that savings in mental health costs will be significant, as one study suggests that frequent consumption of vegetables appear to cut the risk of depression by more than half.

In summary, given the above evidence, driving national acceptance and uptake of a plant-based diet could assist in reducing the rise and prevalence of mental disorders and their associated costs. At a personal level, a shift to vegan diet should not cost any individual more than their previous meat, egg, and dairy-based diet, and may possibly offer much improved quality-of-life outcomes.

Full references for this section can be found here: https://veganaustralia.org.au/fruit_and_veggies_can_make_you_happier

Note that in this section the phrase "chronic disease" refers to "chronic physical disease", such as heart disease, stroke, diabetes, obesity, arthritis, osteoporosis, depression and cancer.

Whole food plant based diets have been strongly correlated with protection against cardiovascular disease, some cancers, obesity, hypertension, type 2 diabetes, depression and anxiety and possibly rheumatoid arthritis.

Chronic diseases are the leading cause of illness, disability and death in Australia, accounting for 90% of deaths in 2011. Over the past 40 years, the burden of disease in Australia has shifted from infectious diseases and injury to chronic conditions. These diseases include heart disease, stroke, diabetes, obesity, arthritis, osteoporosis, depression and cancer.

The situation is dire, with around half of people aged 65-74 suffering five or more chronic diseases, increasing to 70% of those aged 85 and over.

Up to 80% of these diseases are caused by lifestyle behaviours, with diet and nutrition being a primary factor.

The health system should recognise the pivotal role of nutrition in prevention of chronic disease. It should take into account scientific research that shows that consumption of animal products in anything other than small amounts on an occasional basis is linked to a higher risk of overweight and obesity, coronary heart disease, type 2 diabetes, hypertension, metabolic syndrome and cancer, especially of the colon, gastrointestinal tract and prostate.

Vegans, who consume no animal products, enjoy the highest level of protection against all these diseases. See Beyond Meatless, the Health Effects of Vegan Diets: Findings from the Adventist Cohorts.

Currently, government health bodies do not make clear the link between risk factors, such as high blood pressure, high blood cholesterol, obesity and impaired glucose tolerance, with the consumption of animal products. Failing to make this link explicit inclines both health professionals and lay people to the false conclusion that these risk factors are beyond their control, and require medical or surgical intervention.

The health system currently focuses on delivery of medical care for management of chronic conditions, neglecting the substantial literature demonstrating that many of these conditions can be managed more effectively through adoption of a wholefood plant-based diet. These conditions include advanced coronary artery disease, high blood pressure, type 2 diabetes and various autoimmune diseases. Managing these conditions with a wholefood plant-based diet can result in substantially reduced economic costs for both individuals and society as a whole, not to mention substantial improvement in the quality of life of patients.

Rather than showing that medical management of chronic conditions is the only possibility, extensive evidence also exists that a wholefood plant-based diet can reverse some chronic conditions rather than just manage them.

A wealth of scientific literature exists indicating that switching to a wholefood plant-based diet is more effective for weight loss and for reduction of elevated blood pressure, cholesterol, triglycerides and glucose than more modest dietary changes, and in many cases, is more effective than medical management. See the following references.

A wholefood plant-based diet has even been found to reduce painful diabetic neuropathy, a condition for which no effective medical treatment exists. See A dietary intervention for chronic diabetic neuropathy pain: a randomized controlled pilot study and Regression of Diabetic Neuropathy with Total Vegetarian (Vegan) Diet.

Even mental health appears to be improved on a wholefood plant-based diet, with a recent study showing reduced depression and anxiety and improved workplace productivity. See A multicenter randomized controlled trial of a nutrition intervention program in a multiethnic adult population in the corporate setting reduces depression and anxiety and improves quality of life: the GEICO study.

The WHO and European Union have both urged that chronic disease prevention and control considerations should be integrated into policies across all government departments, and that fiscal policies should be employed to promote healthy eating, such as Denmark's saturated fat tax, Hungary's "junk food tax," and France's tax on sweetened drinks. See the following references.

Australian governments should follow these leads and should take a whole-of-government approach. The formation and review of policies in each sector that has an impact on health, such as agriculture, education, planning and environment, should explicitly take into account the impact of these policies on prevention and mitigation of chronic disease.

The WHO emphasises this: "National food and agricultural policies should be consistent with the protection and promotion of public health". In Australia this is suggestion is often ignored by government.

The North Karelia Project in Finland provides an excellent example of the effectiveness of a well-planned whole-of-government approach in reducing chronic disease. Coronary heart disease mortality was reduced by 73% among 30-64 year old males, cancer and all-cause mortality were reduced, and general population health was improved through a portfolio of interventions that encouraged movement toward a more plant-based diet with reduced salt and sugar consumption; smoking cessation; and increased physical activity. Individual measures included subsidising dairy farmers to switch to crop cultivation; working with food manufacturers to reduce the amount of fat, salt and sugar in processed foods; and developing innovative school- and community-based nutrition education programs.

Many factors contributing to chronic disease lie outside the health care system and we need to address the factors to effectively deal with chronic conditions. For example, agricultural and fiscal policies should support production and consumption of health-promoting foods while discouraging production and consumption of foods known to contribute to chronic conditions, such as animal products and refined carbohydrates.

Industry partnerships should be urgently developed to produce beneficial health outcomes. A successful model can be found in the UK's Food Standards Agency's collaboration with the food industry to devise a program of voluntary salt reduction which achieved a 15% drop in 24-h urinary sodium over 7 years. See Salt reduction in the United Kingdom: a successful experiment in public health.

Health and education bodies should ensure adequate nutritional literacy for health and medical professionals, particularly awareness of the proven benefits of a plant-based diet in preventing and reversing many chronic diseases. See Nutritional update for physicians: plant-based diets.

Health professionals should also be trained in skills to counsel clients to adopt a well-planned plant-based diet for both primary and secondary prevention purposes. This is is especially need for those at heightened risk of or already diagnosed with chronic conditions.

A whole-of-government approach and strategic partnerships with industry are required to ensure that at-risk populations throughout Australia have access to affordable fresh fruits and vegetables, whole grains and legumes. There should also be available culturally-appropriate support to adopt healthy, plant-based eating patterns that will reduce their risk of chronic conditions and improve their management.

To ensure health policies are effective, we need to ensure that how we measure progress is relevant. There should be an emphasis on programs that support the prevention of chronic diseases through diet. Progress towards this can be checked through measures such as an increase in the number of medical schools which have compulsory training in therapeutic nutrition; improved knowledge of the application of therapeutic nutrition among health care practitioners; and more facilities in hospitals, outpatient clinics and schools which focus on patient/community education in both the theoretical and practical dimensions of wholefood plant-based eating. The references provide examples of such initiatives that are already operating in hospitals, and in schools. See the following references.

Other measures include reduced mean population intake of animal products, refined carbohydrates and vegetable oils; increased mean population intake of protective plant foods especially whole fruits, vegetables, whole grains and legumes; and increase number of children receiving a nutritious plant-based diet.

Other measures should include access to nutritious food and competency in healthy meal planning, such as the number of at-risk communities with a grocery store within walking distance; number of schools that have a kitchen garden and healthy food preparation program; number of communities that have community gardens and low-cost, culturally sensitive cooking classes that teach wholefood plant-based nutrition.

The current narrow focus on addressing the prevention and treatment of chronic conditions through the health system is out of step with World Health Organization and European Union policies which urge a whole-of-government approach.

A whole-of-government approach is required to achieve prevention of chronic conditions, with the health, agricultural, education and planning and environment departments playing primary roles. Co-ordination between these sectors is essential to ensure the generation of policies that positively impact on individuals' and communities' risks of developing chronic disease.

Encouraging the adoption of a wholefood plant-based diet by all Australians would dramatically reduce risk factors for many chronic conditions, including obesity, type 2 diabetes, ischaemic heart disease, many types of cancer and some mental health conditions.

For those already suffering from chronic conditions, incorporation of a wholefood plant-based diet into their treatment plan is a powerful secondary prevention strategy, and may result in reduced medication usage and in some cases, reversal of the condition.

Making a whole food plant based diet more accessible, acceptable and convenient for all Australians will reduce the risk of chronic disease and therefore reduce the incidence of mental ill-healt

Unsubscribe at any time. Your details are safe, refer to our privacy policy.

© Vegan Australia | Registered as a charity by the ACNC | ABN 21 169 219 854