This report forms part of the "Moving to a vegan agricultural system" series which examines how a move to an agricultural system where no animals are used would impact sectors such as the economy, employment, land use, the environment and food security. This part outlines impacts on land use and looks at options for reusing land currently used for animal agriculture.

It begins with a description of how land is currently used for animal farming in Australia. It quantifies how much land is used and what types of land is used. As well as land used for grazing animals, it includes land used for production of animal feeds, such as fodder crops and crops for grain fed to farmed animals.

It then describes how this land could be reused for other purposes, such as plant agriculture, reforestation, natural regrowth, etc. This includes looking at alternative industries that could be developed, including both expansion of existing plant-based industries as well as new industries.

Since European settlement, the Australian continent has been extensively modified by animal agriculture, with livestock (mainly cattle, sheep and dairy) grazing native or modified pastures on 54% of the continent. About 3.8% of land is used to grow plant foods for humans.

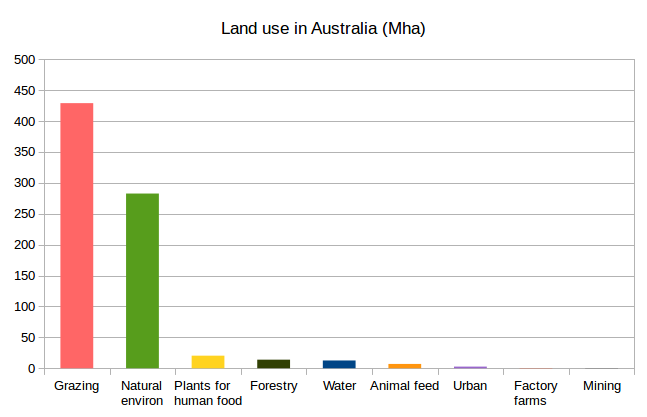

The area of the Australian continent is about 770 million hectares (Mha). Of this, 415 Mha (54%) are used to graze beef, sheep and dairy. In addition, 3 Mha are used for fodder crops to be fed to farmed animals and 4 Mha are used to grow grain to be fed to farmed animals (see Beyond Zero Emissions Land Use Report (BZE LUR) p154 and p169). This compares to the 29 Mha used to grow plant foods for humans (both domestic consumption and export).

While this report concentrates on the situation in Australia, it is interesting to compare it with the global position. Grazing land for ruminants accounts for 26 percent of the world's ice-free land surface, and worldwide, about 100 million hectares of land is used to grow crops for livestock.

Land used for grazing is often on land that was originally forest or woodland. This land is usually cleared before use and sometimes regularly re-cleared or burnt to make it more suitable for cattle and sheep grazing.

As an example of the clearing that occurs, over the last two decades about 9 Mha of land in Queensland was cleared. 93% of the clearing was to establish pasture for livestock grazing. Most of the land cleared was old growth forest, while the rest was regrowth, which can be regularly cleared every 3 - 6 years. "The 'ball and chain' method of clearing land, involving a large metal ball as an anchor connected to a heavy chain with bulldozers raking the chains to uproot large swaths of vegetation at a pass, was used extensively. This practice continues today." (see BZE LUR p21,23)

Much of the land used for grazing is grassland that is regularly burnt to make the land more suitable for grazing. 46 Mha of grasslands are burnt annually (see BZE LUR p51).

The below graph summarises the relative areas of land use in Australia at present. The dominance of animal agriculture industries is evident.

All farmed animals are naturally plant-eaters and many of them graze directly from the ground. However, they also consume a surprising quantity of plant food grown elsewhere, such as fodder and grain (wheat, etc). In fact, farmed animals consume more crops than humans in Australia, eating more than twice as much grain as humans. In other words, two-thirds of crop production for domestic markets are consumed as animal feed. Total animal feed from grains per year is about 9 million tonnes, which is equivalent to about 1 kg per person per day (see BZE LUR p29,30). In the US, animals consume more than seven times as much grain as the American human population.

While the use of feedlots for cattle is not as great as in other countries, the Australian cattle lot feeding industry has expanded significantly over the past 25 years. About a quarter of Australian beef cattle are 'finished' in feedlots for about 50 - 120 days. In 2014-15, 2.8 million grainfed cattle (30% of all adult cattle) were slaughtered. About 30% of feed for dairy cattle comes from crops and large amounts of grain are used in southern Queensland and NSW beef feedlots (see BZE LUR p28,29).

Up to 90% of the food given to farmed chickens and pigs are grains.

Some of these grains, such as wheat and barley, are suitable for direct human consumption while some are grown on land that could be used to grow other food for humans. In general land suitable to grow fodder crops or grain crops for livestock feed is the same as that for food crops. Some feed grains do not meet human food market standards. Alternative uses for these crops are biofuels such as ethanol and green manures. Some plant by-products, such as oil extracted during cotton processing, are used as animal feed but are not suitable for humans (see BZE LUR p30,31). Again, alternative uses for this could be found.

Australia no longer "rides on the sheep's back". The history of farming in Australia is one of continual change responding to changes in technology, the value of commodities and the changing environment. This shows that rural landholders are capable of adapting to changes in conditions and suggests that they will also be able to adapt to a vegan agricultural system.

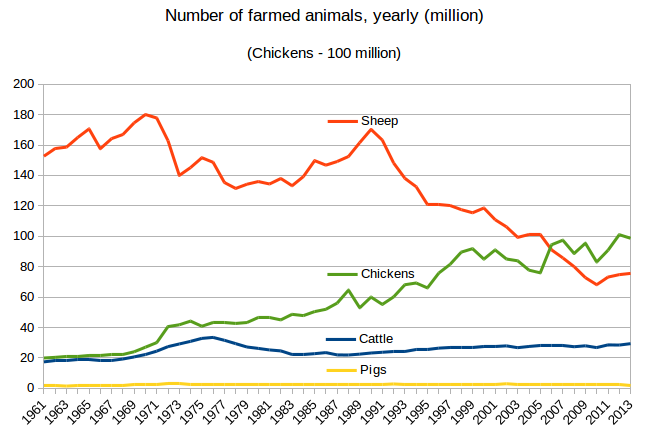

One example of change is the significant decline in the national sheep flock, currently about 75 million, the lowest for more than 100 years. As can be seen in the below graph, the number of sheep in Australia has halved since the 1960s. Due to changing conditions, farmers shift from sheep to crops such as wheat and canola. In 2010, when sheep numbers were at record lows, wheat and canola plantings increased by 50% from the previous year. This shift has had localised impact on producers, but it seems that this major change in the agricultural scene has not had a significant negative impact on the overall prosperity of Australia in that time. While sheep numbers have declined, the number of cattle and pigs has risen gradually and the number of chickens has had a marked increase.

Other changes that have occurred in the Australian agricultural system include the move in some areas from pasture land to wheat farming and to irrigated cropping of cotton and rice (see Pastoral Australia: Fortunes, Failures & Hard Yakka: A Historical Overview). More recently sugar cane farming has taken over some grazing land in the Kimberley in WA.

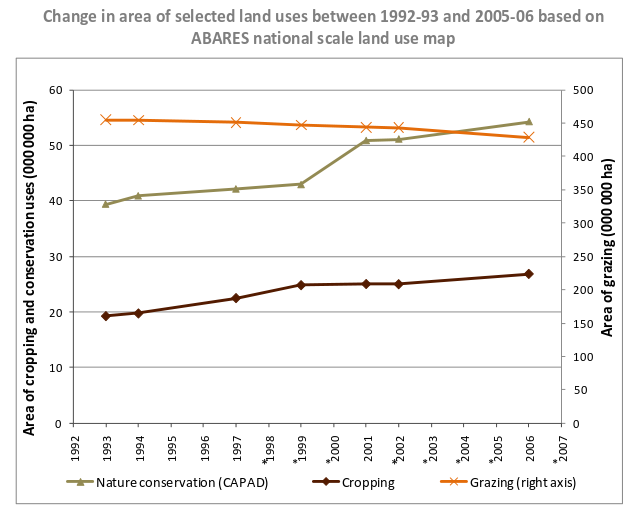

From 1992 to 2005, canola production expanded to most of south-west Western Australia and south-east South Australia. Cotton also expanded its distribution with higher production areas moving south. This may be a response to climatic factors such as water availability (see ABARES land use change report (p14).

Between 1992 and 2005, there was a decrease in agricultural land area in Australia. The majority of the decrease was in the area of livestock grazing, with a reduction of 26 Mha. During the same period the area of cropping increased by 7 Mha. In Victoria, the reduction in grazing land area was 12%, with an increase in cropping area of 8%. These changes for Australia as a whole are shown in the below graph, taken from ABARES land use change report (p11).

As urban areas expand, nearby agricultural production often intensifies, with a shift to higher yielding or higher value production: for example, a move from grazing to intensive horticulture (see ABARES land use change report (p23).

While these changes are not as major as changing to a vegan agricultural system, they do indicate the flexibility of the Australian farming sector. As noted in the book "Pastoral Australia: Fortunes, Failures & Hard Yakka: A Historical Overview", nostalgia for a partly imagined pastoral past and rural life has become part of a popular culture which still imagines farming to be like it was many decades ago. Modern animal farming is very different to how it was for much of Australian history. Industry functions have been mechanised, road transport has replaced droving and smaller family holdings have been amalgamated into large corporate owned operations.

Other factors likely to influence land use change in the future are policy interventions to promote climate change mitigation, including carbon farming (see ABARES land use change report (p21). This topic is covered in the Environment part of this report.

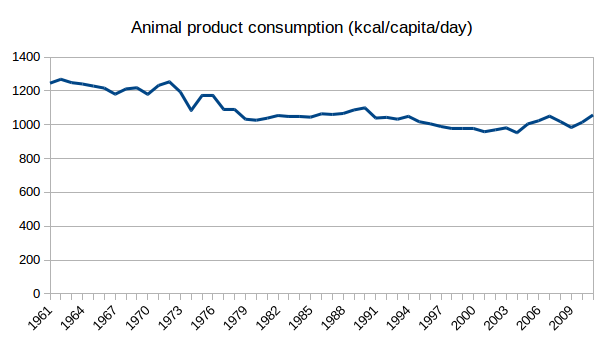

Aside from changes in land use, the tastes of Australians have changed over time. For example, in the mid 1970s, beef and veal consumption was 70kg per person per year. In 2012-13, consumption had dropped by over 50% to 33kg. Since the late 1930s, red meat consumption per capita has reduced by about 46% (see BZE LUR p168). This shows that consumers also respond to changes in social attitudes and economic conditions, in this case reflecting cultural changes, changing attitudes to red meat as well as price fluctuations. The following graph show the reduction in animal product consumption since the 1960s, measured in kcal (Calories) per day.

The changes listed in this section are evidence that farming is responsive enough to handle a shift to a vegan agricultural system. While it is true that much semi-arid and arid zone grazing land is not suitable for plant agriculture, these areas already have a very low yield and their return to a natural state would not cause a significant reduction in food production. Other areas used in animal agriculture are suitable for cropping for human use, especially land that is currently producing fodder and animal feed.

Under a vegan agricultural system, food nutrients currently obtained from animal products will no longer be available. These nutrients will need to be produced by expanding agriculture used to grow plants for humans.

This section will show that there is ample capacity to replace the animal protein foregone with protein sourced from plants by estimating the area of land that is currently used for animal agriculture that could be reused for growing food plants for humans. Land currently used for animal agriculture includes land used for:

One way to estimate how much land could be moved from animal agriculture to plant agriculture is to look at the intensity of current agriculture.

Animal agriculture is carried out in regions covering a broad range of environmental and climatic conditions, not all of which are suitable for growing plants. In agricultural analysis, Australia is often divided into intensive and extensive land-use zones. The intensive zone covers eastern Australia and south-west Western Australia. The main agricultural activities in the intensive zone are cropping, pastoral production and dairying, with an average annual value of agricultural production of about $193 per hectare. The rest of the continent makes up the extensive land-use zone. The extensive zone is arid or semi-arid and is not suitable for cropping. The main agricultural activity is grazing sheep and cattle on native vegetation, with an average annual value of agricultural production of only $3.35 per hectare (see BZE LUR p151,154). In parts of Northern Australia the land is used very inefficiently by raising cattle, taking up to 50 hectares to support just one animal (see BZE LUR p128).

Since the extensive zone is not suitable for plant agriculture, expanded plant production must occur in the intensive land-use zone. The intensive zone has a high biological productivity and offers flexibility in land use choices. Much of the land currently used for intensive grazing and dairying could be used for growing food plants for humans. The area of the intensive zone is 298 Mha and of this 100 Mha are cleared. 27 Mha of this are currently used for growing plants. This leaves about 73 Mha in the intensive zone, some of which is used for pastures for meat and dairy production which would be suitable for plant production. At least 4 Mha of this is used as grazing land for dairy businesses and so would be ideal for plant farming. It not straightforward to derive from these figures the area of land that could be used for growing food plants for humans, but we can get some idea by knowing that both Victoria and Tasmania are entirely within the intensive zone and currently use 6.3 Mha and 1.2 Mha respectively for grazing. Much of this land would be ideal for plant farming. The area for these two states could be extrapolated to other states.

Another way to estimate the area of land that could be moved from animal agriculture to plant agriculture is to look at how much grazing is done on "improved pastures", which are defined to be pastures sown with introduced species, such as grasses and legumes which have higher levels of protein and energy. Data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics show that grazing on improved pastures occurs on 66 Mha of agricultural land while the Department of Agriculture data shows that grazing occurs on 71 Mha of modified pastures and 0.6 Mha on irrigated pastures. While some of this land is currently cropped on an opportunity basis when enough rain falls, other areas suitable for cropping are not currently cropped. It is difficult to estimate how much land this covers.

In another way of looking at it, according to the Australian Bureau of Statistics, two thirds of the national sheep flock are located in regions that have a largely Mediterranean climate that is favourable for the production of improved annual pastures and is suitable for cropping. These regions total about 35 Mha.

An accurate estimate of how much land could be moved from animal to plant agriculture is beyond current research capabilities. This is a big job and would require expert Geographic Information System (GIS) knowledge to combine many different layers of spatial data, including current GIS datasets for land use, areas of arable land and cleared land. It would take considerable effort to gather these datasets and to perform the analysis, taking into account problems with resolution, boundary mismatch and a multitude of data sources.

In summary, although these are only rough estimates, we can say that many 10s of Mha of land could be converted from animal production to plant production if required. This consists of about 3 Mha used for fodder, 4 Mha used to grow grain feed, 4 Mha for dairy grazing and a good proportion of the approximately 60 Mha used for grazing on improved, modified, irrigated and/or Mediterranean climate pastures.

The previous section estimated how much land would become available to grow plant foods for humans if animals were no longer farmed. This section will estimate how much extra plant food would be required to feed Australians if no animal products were consumed. One way is to look at the Australian nutritional guidelines for the amount of each food group required for the average Australian. According to the guidelines most of the recommended diet consists of the fruit, vegetables, legumes and grains groups. Groups that contain animal products are the protein food group (3 serves per day) and the milk or alternatives group (another 3 serves per day). The main macro nutrient in these animal products is protein. The standard serving sizes states that the recommended daily intake for protein is about 60g. This is similar to the value given by the Dietitians Association of Australia which states that the average adult requirement for protein is 50g.

These recommended requirements are somewhat lower than actual consumption. The United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization estimates that in Australia the total protein supply is about 100g per person per day, with protein from animal products making up about 70g of this. This is confirmed by meat consumption data. Australians consume around 111kg of meat per person per year which is equivalent to 67g protein per person per day, assuming average meat protein content of 22%.

Combining the largest value for animal protein consumed per person per day (70g), with the population of Australia (24 million), indicates that an extra 613,000 tonnes of protein needs to be grown per year. To provide this protein from plant sources would require growing legumes and grains such as chickpeas, beans, lentils, rice, oats and wheat. As stated in the Australian Dietary Guidelines, legumes, beans and lentils "provide a valuable and cost-efficient source of protein".

According to Pulse Australia, the protein content of pulses, including chickpeas, beans and lentils ranges from 13% to 32%, with an average of 22%. The protein content of wheat is about 15% and of soybeans 35%. Using the average value of 22% results in an extra 2.8 million tonnes of crops required to provide the required amount of protein. Assuming a yield of 1.4 tonnes per hectare (can be over 2.0 tonnes per hectare for cereals) this means an extra 2 Mha of land would need to be converted to grow crops for domestic human consumption.

As well as domestic consumption, it is important to replace exports of animal products, so that overseas consumers are not adversely affected in terms of protein consumption. Australia exports 60% of all its agricultural production, most of which are plant products. About 60% of its beef and sheep production is exported, much of which goes to developed countries. Australia's main animal product exports are beef (1.0 M tonnes per year) and sheep (261,107 tonnes per year). Very little Australian chicken meat is exported and Australia imports more pig meat and fish than it exports, so these are not included. This totals 1.26 M tonnes of meat exported, which is equivalent to 0.28 M tonnes of protein, assuming an average meat protein content of 22%.

Using as above an average legume and bean protein content of 22% and a yield of 1.4 tonnes per hectare, results in 0.9 Mha of land required to grow crops for export. Adding this to the 2 Mha required to grow crops for domestic consumption results in 2.9 Mha in total for extra crops required.

Comparing this 2.9 Mha with the 10s of Mha of land that could be converted from animal production to plant production, shows that there would be plenty of land available. By removing animals from agriculture more food could be produced for more people, as suggested by the BZE LUR (p154): "The sheer extent of land used to grow feed for animals suggests that there is significant capacity to reduce the footprint of our agriculture without effects on food produced for humans." As mentioned above, the land used to grow fodder and grain crops for animal feed (about 7 Mha) is generally the same type as that required to grow food crops for humans.

As mentioned earlier, animal agriculture uses over 415 Mha (well over half) of Australia's land mass, consisting of about 300 Mha in the extensive zone and 100 in the intensive zone. The section above estimated that about 2.9 Mha would be required to grow the extra plant foods for domestic and overseas human consumption. This section will discuss other ways to use the land that will become available when animals are removed from agriculture. Only a few possibilities will be covered as this is a large and complex task, with many options and which will require further research. The skilled and knowledgeable rural workforce will be a crucial asset in making this change.

Possible uses include the following, which will be discussed further below. Note that the suggested areas are very approximate.

Much of the land in the intensive zone is multi-use, where crops such as wheat, barley, oats and rice are grown in alternation with sheep and cattle grazing. This land should continue to be used for cropping. Further research needs to be done on whether the manure from the grazing animals contributes to the fertility of the soil and how this can be handled in a stock-free farming system, such as by planting alternative crops to generate green manure. The area of multi-use land is shown as the "Wheat-Sheep Zone" in the image below taken from a paper by The Regional Institute. The area is about 35 Mha.

Much of the grazing land in Australia was cleared from original forest or woodland (BZE LUR p22) and some of this land could be reforested and used for logging. Forestry currently occupies 14 Mha of land and this could probably be doubled using previous grazing and dairying land in the intensive zone. Some information on sustainable forestry can be found at Agroforestry in Australia.

Global warming is one of the greatest challenges facing the world and Australia is particularly vulnerable (BZE LUR p8), having "exceptional sensitivity to climate change" (Garnaut Climate Change Review).

The effects are happening now, with Australia experiencing more extreme heat and longer fire seasons because of increasing greenhouse gas emissions.

Reduction in greenhouse gas emissions is crucial to the future wellbeing of Australia. As discussed in the Environment section, animal agriculture is the source of about half of Australia's greenhouse gas emissions and so removing animals from agriculture will go a long way to help Australia quickly reach its emissions reduction targets. In addition, the land that is currently used for grazing animals will be able to be revegetated and thus capture atmospheric carbon in vegetation and the soil. Sequestering carbon dioxide on their land could earn revenue for farmers and landholders, but this would depend on society as a whole contributing to pay for this service and ensuring they are paid fairly (BZE LUR p3). Since much of this carbon sequestration would occur in the arid extensive zone formerly used for grazing, it would be a useful added income to rural communities in remote areas.

It is important that these landscapes are treated as carbon stores and managed to maximise carbon sequestration and retention. Indigenous, landholder and scientific land management expertise should be applied to ensure that sequestered carbon is held long-term and risk of re-emission due to wildfire, disturbance or drought is minimised. (BZE LUR p152)

The BZE Land Use Report estimates that a zero carbon agricultural sector can be achieved by revegetating 115 Mha of Australia's cleared and heavily modified agricultural land, 33 Mha in the intensive zone and 82 Mha in the extensive zone (BZE LUR p135). In making this estimate, the BZE Land Use Report assumes ruminant farmed animal numbers are reduced by only about 20% and thus still make a large contribution to greenhouse gas emissions. If instead there was a 100% reduction in farmed animal numbers, there would be a much larger reduction in emissions and thus revegetating 115 Mha would sequester much more carbon than would be emitted by the agricultural sector. The land use sector would then become a sink for emissions from other sectors, such as power generation and transport.

The Australian government is encouraging farmers to create permanent mallee plantings in areas of low rainfall, as part of the Carbon Farming Initiative, which gives landholders carbon credits for storing carbon or reducing greenhouse gas emissions on the land.

Biochar is charcoal made from plant matter, such as short rotation woody crops, that is used to improve soil fertility and sequester carbon. The use of biochar has the potential to achieve continuous draw-down of carbon dioxide, particularly for woody plants like mallee that grow multiple stems which regrow after harvesting (coppicing). Atmospheric greenhouse gas concentrations can actually be reduced. Short rotation woody crops can be harvested and re-harvested and so have far greater potential to provide ongoing carbon sequestration than permanent plantations. It is unclear how much land could be used in this way, but it could be several million hectares (see BZE LUR part 6.4).

Much of the land currently used for grazing animals will probably not have a valuable productive economic use if animals are removed from agriculture. This land, in the extensive zone, is not suitable for any of the more economic uses listed above. However, if it is rehabilitated and allowed to regrow, it will be valuable in other ways, with positive benefits such as

This section looks at examples of how land previously degraded by animal agriculture has been revitalised, often by simply removing the farmed animals from the land.

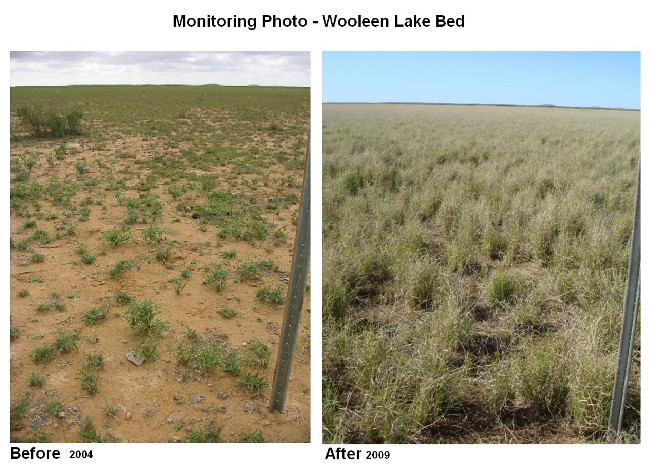

One interesting example of a change in land use in line with a vegan agricultural system is the destocking and regeneration of the rangelands at Wooleen Station in Western Australia. This land had been over-grazed for over 100 years resulting in most of the prime land being in poor or very poor condition with some of it being badly eroded and degraded to the point where it is never expected to recover. The situation at Wooleen is typical of neighbouring areas and in fact of much of the Australian rangelands.

In 2007, the leaseholders of the 200,000 hectare station "Wooleen" decided to completely destock the entire property for four years. The re-establishment of the vegetation "has progressed much better than expected". A multitude of plants re-appeared, including the slow growing, but sturdy, saltbush. This regrowth occurred because cattle were no longer grazing and despite a long drought. Some plants returned to areas where they were never expected to grow. Plant and animal species threatened with extinction also began to return. Perennial plants, crucial to restoring the land, were among those re-established.

During the time when no farmed animals grazed, grasses were planted and infrastructure was changed to replicate the natural systems that had been lost, culminating in the Roderick River flowing clear of eroded sediment for the first time in living memory. In just four years, a red river had been turned clear by removing farmed animals from the land and restoring some of the natural systems. "Nature is bouncing back." Please see video presentation on the regeneration at Wooleen.

The image above shows Wooleen leaseholder David Pollock transplanting native grasses into flowing creek lines after good rains.

In Australia, most grazing land is owned by the state and leased to farmers. It is interesting to note that a condition of the lease is that the land must be stocked with farmed animals. The majority of income must come from grazing. Other uses, such as tourism, are not encouraged. In fact, the leaseholders of Wooleen had to wait one year for permission from the Pastoral Lands Board to remove stock from the property.

The success of this case study in such a short time suggests that it may be possible to restore land quickly and without great expense in many parts of Australia.

La Trobe University in Melbourne has been restoring a large area of land which was previously used to graze sheep and for dairying. The 30 hectare La Trobe Wildlife Sanctuary was set up in 1967 as a project in the restoration and management of indigenous flora and fauna. Much of the restoration work is carried out by volunteers, who revegetate, weed, maintain the seed bank and manage biodiversity. Wetlands have been restored to the area. After revegetation has created nesting places, wildlife is returning to the area, although it can take up to 150 years for nesting hollows to be created naturally in old growth trees.

The image shows a volunteer collecting seeds at La Trobe Wildlife Sanctuary.

The remediation of Burrima wetlands in central NSW is a fascinating case study that exposes the deadly impact animal farming has had on the Australian environment and the fairly rapid improvement brought about by removing farmed animals from the land.

The Burrima conservation area has a number of vegetation areas and each has been affected by prolonged sheep and cattle grazing in different ways, such as by denuding the understorey plants of the woodland areas, trampling the reed beds and causing serious erosion, and removing all vegetation and exposing the topsoil, which was then blown away, resulting in bare claypans. 60% of the reed beds of the South Marsh (around 2,200 hectares) were lost between 1840 and 1963.

The restoration of the area began in 2005 with "a plan to de-stock Burrima and return the land to sound environmental health." Removing the cattle allowed the native understorey plants to consolidate and reclaim the woodlands. Native grasses were also reintroduced.

In the River Red Gum area, removing the cattle allowed the reeds to re-grow dramatically, forming dense thickets that conserve and filter water. When dry, they form a thick mulch covering the soil. The revived reeds protect against erosion, trap and spread water, and reduce evaporation.

These restoration measures enabled the natural wet-and-dry cycle to return to Burrima, improving the flora and fauna health of the land.

The image shows the reed beds on the boundary of Burrima in 2005, clearly showing the damage caused by grazing.

Read the full article Burrima - a case study in sound ecological management by the National Farmer's Federation and find out more about the Macquarie Marshes Environmental Trust.

Run-off caused by animal agriculture is devastating the Great Barrier Reef. In 2016, the Queensland Government bought Springvale cattle station in Far North Queensland. All cattle have been removed and degraded grazing land is being restored to help protect the reef from silt.

The Government said Springvale Station near Cooktown was one of the biggest polluters in the Normanby catchment, with a Griffith University study finding it generated 460,000 tonnes of sediment run-off every year.

The 560 square kilometre property has been declared a nature refuge. Conservation groups hailed the "unprecedented" land purchase as a win for the World Heritage-listed area.

Watch the ABC news report of the government plans for the property.

Environment Minister Steven Miles said steps will be taken to restore badly degraded grazing land on the property, which generated 460,000 tonnes of sediment run-off every year. The property was responsible for 40 per cent of sediment from gully erosion in the Normanby basin. He said eroded gullies could be "smoothed out" and planted to grass.

Dr Miles said the acquisition was also critical to conservation as Springvale was home to threatened species the southern cassowary, northern quoll and red goshawk.

The image shows erosion in a gully at Springvale Station.

Ideally we would like to be able to give accurate quantitative recommendations for how land should be used in a vegan agricultural system. In the section "Reusing land currently used by animal agriculture" above, we have tried to be as accurate as possible, but further investigation needs to be done in this area.

Unsubscribe at any time. Your details are safe, refer to our privacy policy.

© Vegan Australia | Registered as a charity by the ACNC | ABN 21 169 219 854